The headlines say that congressional Democrats were the big winners of a surprise deal with President Donald Trump at the White House on Wednesday. Senate and House Minority Leaders Chuck Schumer and Nancy Pelosi seemingly got what they wanted from President Trump: emergency funding for Hurricane Harvey, an agreement to fund the government at existing levels, and a clean raise of the debt ceiling. But some progressives aren’t so sure that Democratic cooperation was a win for Democrats. Rep. Luis Gutierrez (D-IL) is one of a handful on the left arguing Democrats actually gave up more than they got on Wednesday.

In last Wednesday’s Oval Office meeting, President Trump made an abrupt about-face, siding with Chuck Schumer and Nancy Pelosi on their proposed debt-ceiling timeline.

Gutierrez says funding the government should be contingent on protecting the 800,000 young immigrants made vulnerable by Trump’s decision to rescind the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrival Program. Democrats have a conundrum: Should they seize the opportunity to shape legislation by offering Democratic cooperation with Republicans? Or are they better off sticking with full resistance?

Rep. Luis Gutierrez (D-IL) and activist groups think Democrats should tie protecting the DREAMers to must-pass emergency measures. Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images

Resistance has been successful, Democrats have saved the Affordable Care Act while driving Trump’s approval numbers down into the 30s, and all the grassroots energy outside the Beltway is with the left. But with 10 of the 11 Democratic Senators who represent states that President Trump won up for reelection, Democratic cooperation has to be an option 100 percent resistance is not practical. Democrats have to know when to offer Democratic cooperation and when to obstruct, Politico has published the following “Handy Guide” to help Democrats determine when to hold and when to fold:

But with 10 of the 11 Democratic Senators who represent states that President Trump won up for reelection, Democratic cooperation has to be an option 100 percent resistance is not practical. Democrats have to know when to offer Democratic cooperation and when to obstruct, Politico has published the following “Handy Guide” to help Democrats determine when to hold and when to fold:

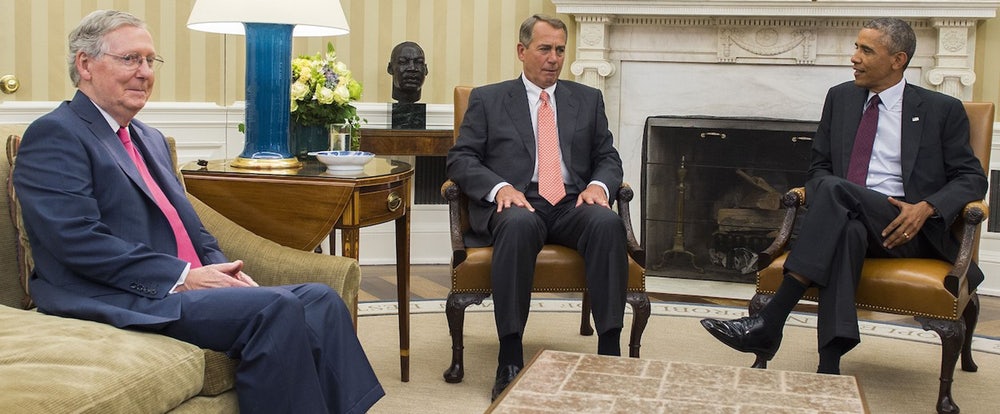

1. Don’t Forget: Even Republicans Cooperated With Obama Sometimes

“We were a 10-year opposition party,” Speaker Paul Ryan sheepishly admitted last week. While it’s true that Republican leaders privately pledged on Barack Obama’s inauguration day to “challenge them on every single bill and challenge them on every single campaign,” and Senate Majority leader Mitch McConnell famously vowed to make Obama a one-term president, it’s also true in executing that obstructionist strategy, there were times when Republicans, in groups large and small, found it necessary to cooperate.

Republican Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (left) former Republican Speaker John Boehner (center) confer with former Democratic President Barak Obama

In Obama’s first term, Republicans helped pass bills to regulate food safety and reduce crack cocaine sentences, mainly with voice votes. Eight Senate Republicans voted to repeal “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” Three provided critical votes to not only pass but also shape the Recovery Act, as did Republican Sen. Scott Brown for Obama’s prized Wall Street reform.

Cooperation diminished once Republicans took over the House in 2011, but it did not disappear. Republicans played hardball around raising the debt limit, but settled for an awkward compromise to reduce the deficit without overhauling entitlements. Republicans capitulated after initially resisting legislation to aid domestic violence survivors and Hurricane Sandy victims. Even the infamous 2013 shutdown ended with surrender.

The common thread that runs through most of these examples is that Republicans rarely bragged about their occasional lapses into bipartisanship. They aimed for the bare minimum of assistance to avoid being charged with cruelty, and otherwise made governing as difficult for the Democrats as possible. They were mostly content to let government flail and flop.

The Democratic Party, rooted in the belief that government should actively promote the common good, doesn’t have the same ideological luxury. While Democrats still need to limit Democratic cooperation with Trump to a minimum, their minimum has to be set at a higher standard than the Republican minimum.

2. People Love Bipartisanship … But Hate Compromises

At some point, Trump is going to dangle a significant carrot in front of the Democrats seeking to attract Democratic cooperation, most likely, an infrastructure bill. Most Democrats are skeptical because they believe he will mainly eschew direct government spending for corporate tax breaks, which they doubt will create many jobs.

But maybe a desperate Trump moves farther in the Democrats’ direction than they expect. If Trump is going to give Democrats most of what they want, they can’t say no. You can’t look an unemployed worker in the eye and say, “Sorry I didn’t create those infrastructure jobs, but I had to resist Trump.”

However, as the White House is now hinting, Trump’s expected infrastructure offer may be tied to a demand that Democrats support controversial tax reform. A revenue-neutral tax reform package—with both tax cuts and new revenue—could pass through the budget reconciliation process, which would prevent Democrats from filibustering, but might fail to unify Republicans and require Democratic votes. A budget-busting tax cut-only bill could not pass through reconciliation, and would need at least eight Senate Democrats to avoid a filibuster.

Democrats should find the will to resist such a “grand bargain” and give no Democratic cooperation, even if there is a great pressure to prove their bipartisanship and end “gridlock.” Most people may say they want Washington to work, but often when Washington does work, they end up hating the compromises Washington produces.

Exhibit A: the hated “sequester.” Did you ever hear any politician in Washington take credit for budget cuts that came out of the 2011 debt limit increase compromise? Of course not, even though it passed with Democratic cooperation in both houses. Many liked deficit reduction in theory, but didn’t like the cuts to the military and social programs that made it reality. The sequester was a fallback position after a more ambitious “grand bargain” of entitlement cuts and tax increases spooked Congresspersons in both parties.

A carefully balanced grand bargain of infrastructure spending and corporate tax cuts will likely be battered by forces on the left and the right highlighting the bill’s many weaknesses, real or imagined. Enthusiasm from either party’s political base would be nil. And as Democrats learned the hard way from the 2009 Recovery Act, infrastructure spending often doesn’t produce an immediate political payoff, because there aren’t that many “shovel-ready” projects that create jobs instantaneously, so taking the risk on a Democratic cooperation could easily lead to criticism that corporations pocketed tax cuts while infrastructure jobs failed to materialize.

For Democrats to get on board, any infrastructure bill would have to be heavily weighted in their favor. A 50-50 deal won’t do.

3. Play extremely hard to get

At the beginning of Trump’s presidency, Rep. Elijah Cummings—who represents deep-blue Baltimore—went way out of his way to score a meeting with Trump. In the first week, Cummings announced his desire for a meeting on MSNBC’s Morning Joe, which successfully won him a presidential phone call in which they discussed Cummings’ ideas to lower prescription drug prices. Three more meetings followed in early March, after which the Maryland Democrat declared Trump “enthusiastic” about his proposals.

Cummings was not wrong. A few days later, at a Kentucky rally intended to drum up support for the soon-to-die American Health Care Act, Trump alluded to Cummings’ plan to empower Medicare to bargain with pharmaceutical companies: “We’re going to have a great competitive bidding process. Medicine prices will be coming way down. Way, way, way down … I said, we gotta add that to the bill … we’re going to try to add it to this bill. But if we can’t, we’re going to have it right after.”

But the proposal was not tacked on at the last minute, and in turn, Cummings dodged a political bullet.

Negotiate, Compromise, Settle and Agree words on arrow signs to illustrate a diplomatic discussion to reach a mutually approved deal

If his lobbying had resulted in the prescription drug plank, long craved by Democrats, becoming part of the Republican bill designed to obliterate the biggest Democratic health policy achievement in 50 years, Cummings would find himself in a serious squeeze. Democrats would attack him for prettying up legislation they consider abhorrent. Trump would pressure him to vote for the underlying bill, and if Cummings didn’t, that might be the end of his interest in Cummings’ ideas.

Most legislators like to legislate, and may see no harm in making a pitch to the mercurial Trump. But by proactively feeding proposals to this president, you lose control over how he will use those proposals. It’s a recipe for getting played. The only time it will ever be OK for Democratic cooperation work with Trump is if Trump comes begging for votes and Democrats can dictate the terms. Otherwise, it’s hard to trust him.

4. Don’t make government dysfunctional

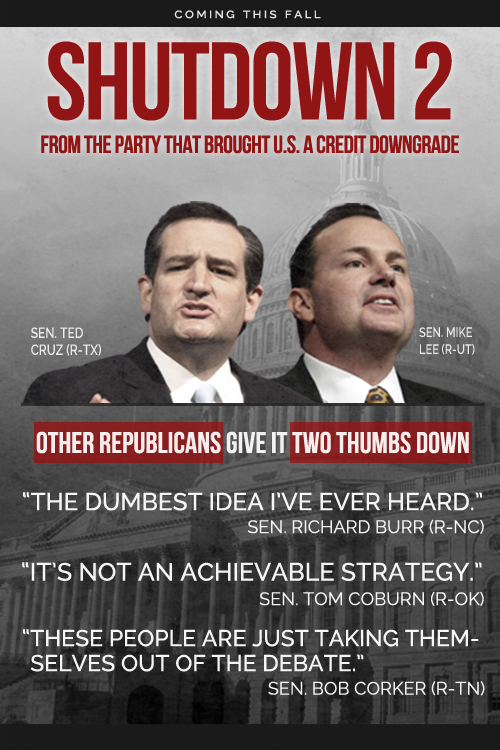

It seems only fair for Democrats to use the threat of a government shutdown and debt default to shake down Trump, after Republicans did it to Obama.

But Democrats will not be able to use that leverage crudely. Unlike for Republicans, touting the benefits of a shuttered government and hysterically mischaracterizing debt-ceiling increases as threats to American solvency is off-brand for Democrats—and even some liberal pundits can be expected to say as much.

The core Republican message is that government doesn’t work, so Republicans have little hesitation in proving the point. Democrats want voters to believe in government. Therefore, playing the lead role in government dysfunction undercuts their objectives.

At the same time, Democrats harm themselves if they come across as patsies. They can’t be sanguine about a spending bill that guts public health agencies while building a border wall. And they can’t play left-wingman for a debt-limit bill saddled with extraneous right-wing policy riders.

So Democrats will need to do more than just resist. As in 2013, they will have convince the public that they are the more reasonable party, and be prepared to deal once Republicans buckle.

Republicans lost the shutdown battle of 2013 because they made a laughably unreasonable demand—junk the health care bill that both passed the Congress and was effectively reaffirmed by the public in the 2012 presidential election. (Those who point to the Republicans’ 2014 midterm election victory as evidence the shutdown worked ignore the beating Republicans took in the polls during the standoff; Republicans recovered only after they surrendered. Furthermore, Obamacare still lives.)

But Republicans were on relatively firmer political ground in 2011 when they pressed Obama for a deficit reduction plan in exchange for Democratic cooperation on the debt limit. After Democrats complained about “hostage-taking” and risking a calamitous default on the debt, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell candidly explained that the debt limit is “a hostage that’s worth ransoming … it focuses the Congress on something that must be done.” Even Obama had embraced a deficit reduction target a year earlier, so Republicans didn’t seem out of line, and they avoided political damage.

But to appear reasonable, Democrats need to lay out reasonable criteria for cooperation. Asking for the moon, then bargaining down, risks the appearance of both sides playing political games with people’s lives.

For example, Democratic leaders could say, “Democrats will support a government operations bill that allows our government to operate. This is not the time to ram through radical policy changes that could upset government functions without robust debate and public input.” A similar principle can be articulated when dealing with a debt-limit increase if Republicans try to tack on extraneous policy riders: “The debt limit ensures the Treasury can pay debts already issued due to past congressional spending. We should responsibly take care of our debt obligations now, and save other policy debates for later.”

That will allow Democrats in the Senate to credibly filibuster a bill that defunds Planned Parenthood, supports a border wall, slashes public health or pushes any other right-wing demand that lacks broad public support. But such a framework also opens the door to talks, on Democratic terms, once Trump recognizes he can’t resolve the impasse if he’s beholden to the far right.

5. If you can get Trump to break a major promise, do it

Trump may be down, but presidents can bounce back. Bill Clinton sank below 40 percent approval in his first six months, as did Ronald Reagan in 1983. Obama limped along in the 40s for much of his first term. All recovered in time for re-election.

The main fear of Democratic compromise is that it could help Trump begin a comeback. But the best kind of deal is the one that can knock him to the canvas for good.

Impossible? Consider the most satisfying bipartisan deal Democrats ever made with a Republican president: the 1990 budget agreement.

Democrats controlled both houses of Congress and insisted that any deal include tax increases to reduce the deficit. President George H. W. Bush’s signature campaign pledge was “Read my lips. No new taxes.” But he could count, and he acquiesced.

The final deal began the partial undoing of Ronald Reagan’s tax reform, bumping the top tax rate up from 28 percent to 31 percent. (It now sits at 39.6 percent after increases signed by Bill Clinton and Barack Obama.) But the only one who politically suffered for the deal was Bush, as conservatives never forgave him for breaking his word. Bush was subsequently wounded in the 1992 Republican presidential primary by Pat Buchanan and lost some conservative voters to independent Ross Perot in the general.

Trump breaks his word all the time, believing he could “stand in the middle of 5th Avenue and shoot somebody” without losing supporters. Already he’s flinched from campaign promises to end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, exit the Paris climate pact and, of course, repeal Obamacare. Hungry for a legislative win, Trump may be convinced he can break another promise. And that may be one broken promise too many.

It may seem implausible that Democrats could ever get Trump to abandon signature proposals like building a border wall, eradicating the Clean Power Plan or cracking down on immigration from war-torn majority-Muslim countries. But if Trump gets increasingly desperate, it can’t hurt to ask.

The most important thing is that Democrats don’t make the same mistake Republicans made during the Obama presidency, becoming total obstructionist and accomplishing nothing substantial of their political agenda. When it comes to the question of Democratic cooperation, Democrats must remember that good political leadership is knowing how, when and what to compromise!