Crystal Patterson was arrested for the first time in her life after a physical fight with her brother-in-law. After Crystal’s arrest, she was booked into the county jail and was told she could be released if she paid $150,000 cash bail. In Baltimore Rafiq Shaw was arrested for allegedly having illegal possession of a handgun. He was told he could be released on a $100,000 cash bail. And Tyrone Tomlin heading home from a construction job is arrested for allegedly having drug paraphernalia, he was told he could go home if he paid $1,500.00 cash bail. All 3 of these people have three things in common:

1) In all 3 cases charges were dropped before they reached court

2) All 3 people spent time in jail for a crime they did not commit

3) Even though neither of the 3 was ever charged or found guilty of the crime they were arrested for, all were left worse off financially

This miscarriage of justice is due to an antiquated practice that’s toxic to equal justice under the law and wreaks financial havoc on working-class Americans.

The practice that’s become toxic to equal justice, is requiring cash bail for minor traffic offenses, misdemeanors and low level non-violent felony offenses. Bail is money or some form of property that is deposited or pledged to a court by a suspect, in return for their release from custody or pre-trial detention. It’s a practice that dates back to medieval England.

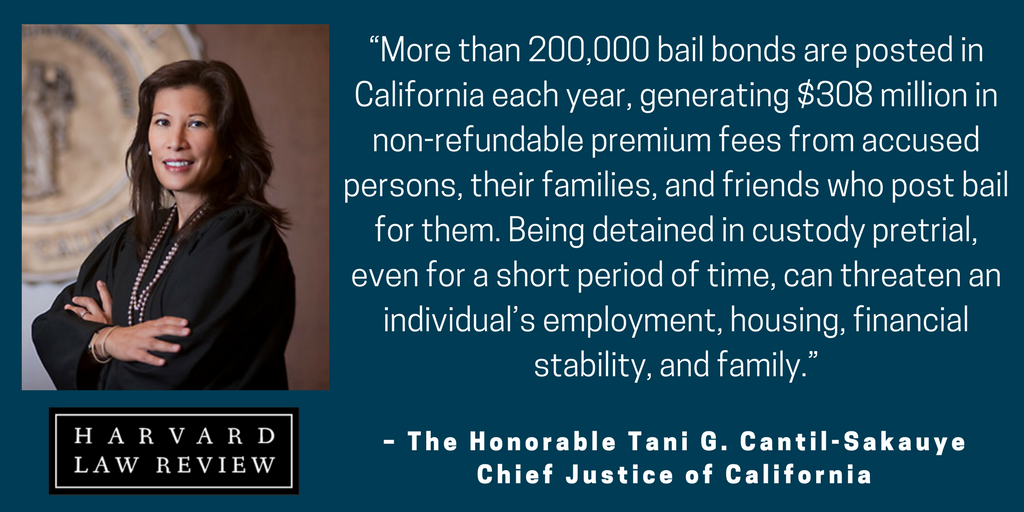

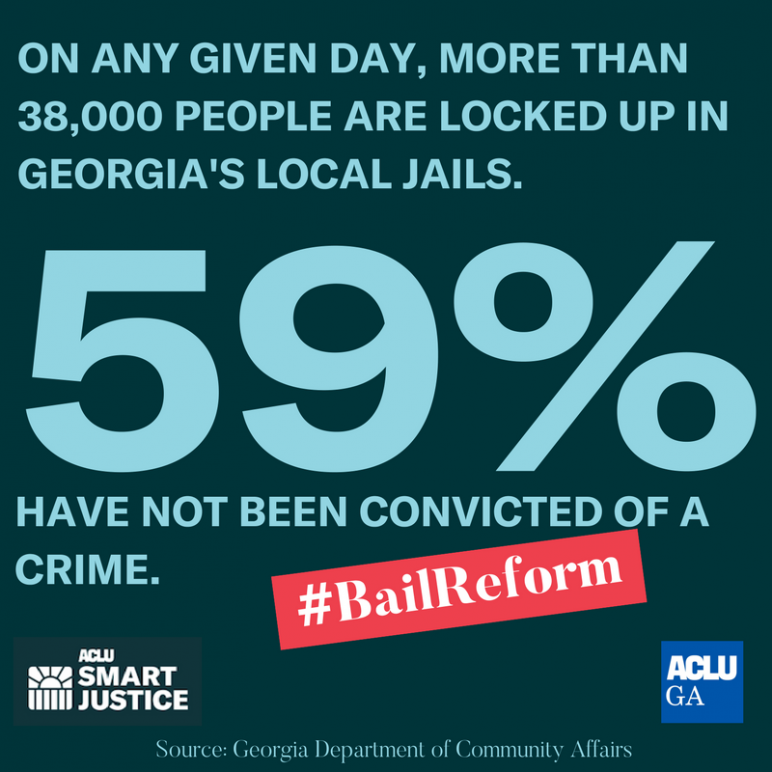

Unfortunately, bail in America has evolved to be a system that denies people with no resources their physical freedom. No one should spend time in jail simply because he or she is poor, but every day about 450,000 Americans sit in jail for that very reason. Despite the constitutional guarantee that everyone is presumed innocent until proven guilty, our current cash bail system forces arrestees to pay an arbitrary amount of bail money to secure release before trial. Those who can afford to purchase their liberty walk free, while those who can’t languish in jail pending trial. The result is discriminatory pretrial detention based on wealth-status, not any meaningful assessment of flight risk or danger to the community.

In the case of Crystal Patterson arrested for fighting with her brother-n-law, a cash bail of $150,000 was set. In order to leave jail, she had to pay 10% of the bail amount, a whopping $15,000 to a bail bondsman who would then post her bail. For people like Crystal who don’t have that type of money, private bail companies offer a predatory option. Crystal could pay 1% of the bail amount, $1,500, and sign a debt agreement to finance the balance of the $15,000 at the maximum interest rate allowable by law. After 31 hours in jail, Crystal scraped together $1,500 signed the debt agreement and went home. Hours after Crystal left the jail, the District Attorney looked at her file and decided there wasn’t enough evidence to file charges. Crystal was never charged with a crime; she never had a single court date; she has no case against her. And yet, she will be paying off the balance of her $15,000 debt — with interest — for years and years to come.

In the case of Rafiq Shaw accused of possession of a firearm, police claim after a search of a car Shaw was driving they found a gun in the glove compartment. It was a discovery that stunned Shaw, who said he has never owned a gun. “And this was my mom’s car,” he proclaimed. Police had no evidence, such as fingerprints, to prove the gun was Shaw’s. He didn’t even have a key to the glove compartment where the gun was found; the cops had to smash it open. After less than a half an hour of deliberation, the jury found Shaw innocent on both counts. But Shaw is still paying for the crime he never committed.

The district court commissioner who handled Shaw’s arraignment set bail at $100,000. His fiancée and his mother scraped together what they had, and Shaw cleaned out his meager savings. They gave it all to their bail bondsman, who agreed to bail Shaw out for a fee of 10 percent, or $10,000. Shaw and his family said they paid the bondsman about $2,000 up front, with a promise to pay $100 a week until the amount was paid in full. Shaw earns $10.15 an hour installing trailer hitches for U-Haul. “I’ll be paying for a long time,” he says. “Like forever.”

Tyrone Tomlin’s case shows the real predicament those with no resources face. Tomlin was arrested basically for being around profiled people at the wrong time. According to the New York Times as he and his friends were talking outside of a store, two plainclothes officers from the New York Police Department’s Brooklyn North narcotics squad, recognizable by the badges on their belts and their bulletproof vests, paused outside the store.

Tomlin broke off to go inside the store and buy a soda. The clerk wrapped it in a paper bag and handed him a straw. Back outside, as the conversation wound down, one of the officers called the men over. He asked one of Tomlin’s friends if he was carrying anything he shouldn’t; he frisked him. Then he turned to Tomlin, who was holding his bagged soda and straw. ‘‘He thought it was a beer,’’ Tomlin guesses. ‘‘He opens the bag up, it was a soda. He says, ‘What you got in the other hand?’ I say, ‘I got a straw that I’m about to use for the soda.’ ’’ The officer asked Tomlin if he had anything on him that he shouldn’t. ‘‘I say, ‘No, you can check me, I don’t have nothing on me.’ He checks me. He’s going all through my socks and everything.’’ The next thing Tomlin knew, he says, he was getting handcuffed. ‘‘I said, ‘Officer, what am I getting locked up for?’ He says, ‘Drug paraphernalia.’ I say, ‘Drug paraphernalia?’ He opens up his hand and shows me the straw.’’

The documentation submitted by the arresting officer, explained that his training and experience told him that plastic straws are ‘‘a commonly used method of packaging heroin residue.’’ Tomlin does have a criminal history of 41 convictions, all of them except for two-decades-old felonies, are for low-level nonviolent misdemeanors — crimes of poverty like shoplifting food from the corner store. Based on his record Tomlin’s Public Defender suggested that the District Attorney’s Office would most likely ask the judge to set bail, and there was a good chance that the judge would do it. If Tomlin couldn’t come up with the money, he’d go to jail until his case was resolved.

After conferring with the District Attorney they were prepared to offer Tomlin a deal. Plead guilty to a misdemeanor charge of criminal possession of a controlled substance, serve 30 days on Rikers Island and be done with it. Tomlin said he wasn’t interested. A guilty plea would only add to his record and compound the penalties if he were arrested again. ‘‘They’re mistaken,’’ he told his Public Defender. ‘‘It’s a regular straw!’’ When the straw was tested by the police evidence lab, he assured her, it would show that he was telling the truth. In the meantime, there was no way he was pleading guilty to anything.

When it was Tomlin’s turn in front of the judge, events unfolded as predicted: The Assistant District Attorney handling the case offered him 30 days for a guilty plea. After he refused, the A.D.A. asked for bail. The judge agreed, setting it at $1,500. Tomlin, living paycheck to paycheck, didn’t have that much money saved up and there was no way he could come up with that amount of money.

Tomlin’s willingness to hold out against the charges was unusual. Across the criminal-justice system, cash bail acts as a tool of compulsion, forcing people who would not otherwise plead guilty to do so. A 2012 report by the New York City Criminal Justice Agency, based on 10 years’ worth of criminal statistics, bears this out. In non-felony cases in which defendants were not detained before their trials, either because no cash bail was set or because they were able to pay it, only half were eventually convicted. When defendants were locked up until their cases were resolved, the conviction rate jumped to 92 percent. This isn’t just anecdotal; a multivariate analysis found that even controlling for other factors, pretrial detention was the single greatest predictor of conviction. ‘‘The data suggest that detention itself creates enough pressure to increase guilty pleas,’’ the report concluded.

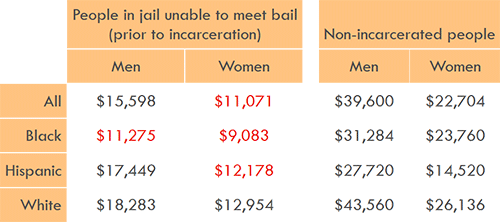

Median annual pre-incarceration incomes for people in local jails unable to post a bail bond, ages 23-39, in $USD (2015), by race/ethnicity and gender.

Awaiting trial at Rikers Tomlin got into trouble, he was jumped by a group of young men. He received medical attention for a monstrously misshapen face and a swollen shut left eye. Three weeks after his arrest, when he returned to court prosecutors handed over a report from the police laboratory, which had tested the drinking straw. At the top of the report, in bold, underlined capital letters, were the words ‘‘No Controlled Substance Identified, Notify District Attorney.’’ ‘‘The judge says, ‘Mr. Tomlin, this is your lucky day, you’re going home”.

By this time Tomlin had lost three weeks of income, was subjected to brutal physical violence and missed Thanksgiving dinner with his family. But he resisted the pressure to plead guilty. His previous convictions all came from pleas, most of them made with cash bail looming over him. He knows the bitter Catch-22 of pleading guilty to get out of jail.

Tomlin’s stand on principle is admirable but at the end of the day, he had no choice but to stay in jail because he couldn’t afford his bail. He is not alone between 1983 and 2014 the proportion of jail inmates not convicted of a crime grew by 200 percent. Growth in the un-convicted jail population has been heightened by an increase in the use of financial bail that many cannot afford. In 1990, 53 percent of felony defendants in large counties were assigned bail, and by 2009, this proportion had grown to 72 percent. Many of these defendants have limited resources and are not able to post bail, remaining incarcerated while awaiting conviction or acquittal.

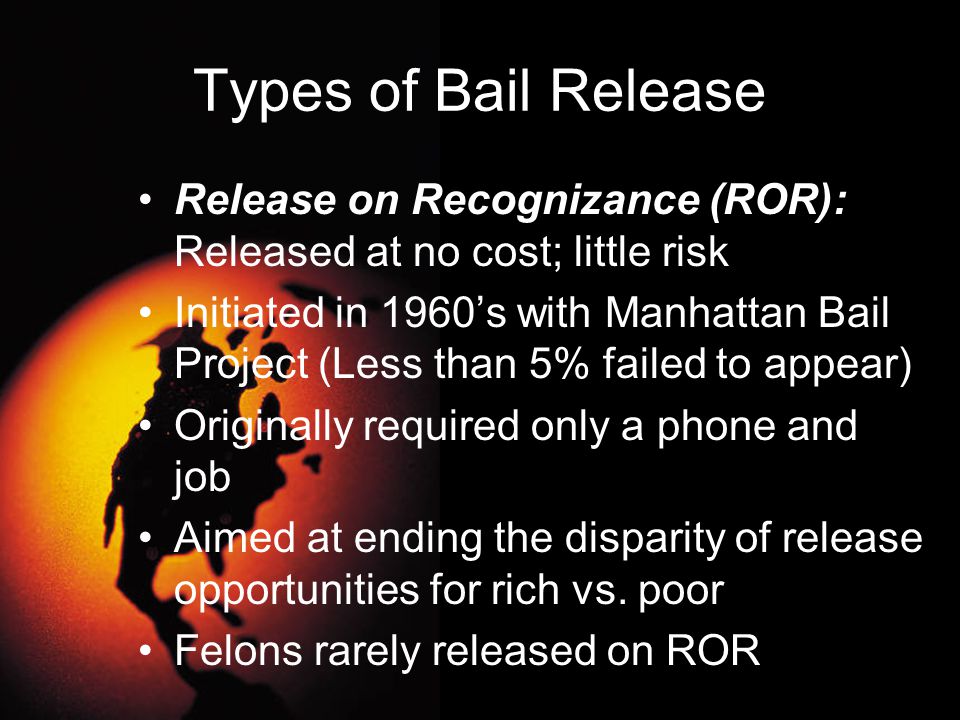

For those wondering what effect on crime eliminating cash bail would have, need look no further than the state of New Jersey. In January of 2017, New Jersey became the first and only state in America to eliminate cash bail. It switched to a system where Judges consider each defendant’s individual risk before deciding to release them or keep them in jail while awaiting trial. The new method addressed a concern long held by criminal justice advocates that too many poor people were stuck behind bars simply because they couldn’t afford to get out. Law enforcement officials also applauded the overhaul, since it allowed judges to keep potentially dangerous criminals locked up until trial. (Previously courts had to issue money bail to almost everybody.)

Before cash bail was scrapped, opponents said low-level defendants released shortly after their arrest would break the law again in large numbers, resulting in a crime wave across the Garden State. That never happened. Preliminary crime statistics from the New Jersey State Police show no major bump in violent offenses across New Jersey. In fact, just the opposite is true: For many serious crimes, the rates are dropping. Rapes and shootings are up slightly across New Jersey, but murders, robberies, and assaults dropped — some by double-digit margins.

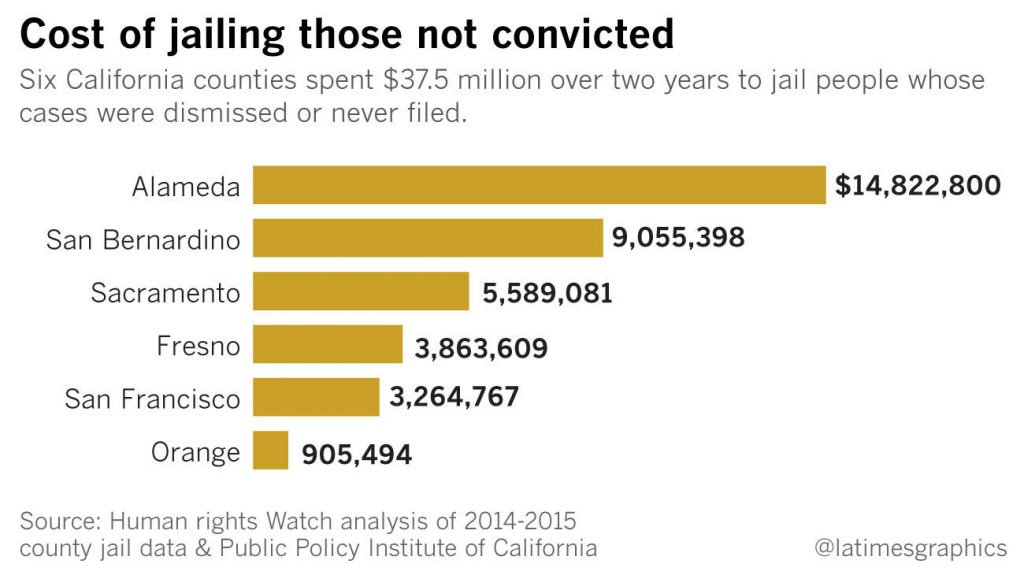

A cash bail detention system has disastrous consequences: overcrowding of local jails, lost jobs, lost housing, poor sanitation and medical care, broken families, and drained local budgets. In many cases, an arrestee may be held longer in jail while awaiting trial than any sentence she or he would likely receive if convicted, causing innocent people to plead guilty to offenses that they did not commit in order to shorten lengthy pretrial detention. Individuals who are detained are not able to assist their attorneys in the investigation of the charges against them, resulting in wrongful convictions and longer sentences.

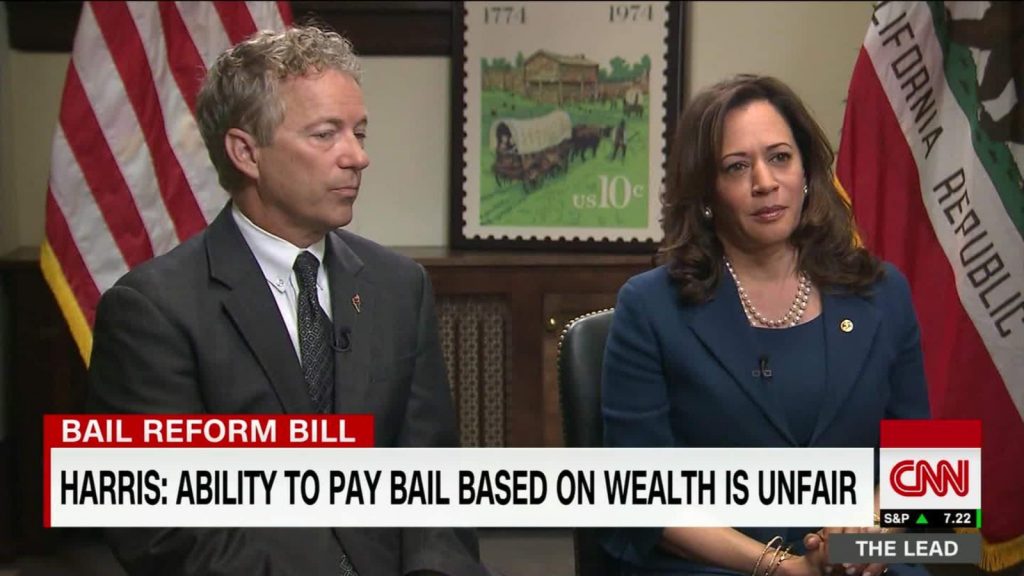

Republican Senator Rand Paul (left) and Democrat Senator Kamala Harris (right) have formed a bi-partisan partnership to reform cash bail

It’s time to kill the cash, and follow New Jersey’s game-changing bail reform efforts so that the only people in America’s jails are people guilty of crimes, and not people guilty of being poor!